Legio XX - Valeria Victrix

The Roman army arrived in Britain in 43AD, settling initially in the south before moving north to subdue the native tribes.

By 79AD, a legionary fortress was built at Chester. This was one of three permanent fortresses in Britain; each was home to an entire legion of between 5,000 and 6,000 men.

The local tribe to Chester was the Cornovii. Before the arrival of the Romans, they were farming the land and producing salt from the brine springs of central Cheshire.

The Romans built roads to allow the efficient transport of troops and supplies and these linked Cheshire to Roman settlements across Britain. Important local routes linked the industrial settlement of Wilderspool near to Warrington, the trading post of Meols on the Wirral coast and the salt making sites of central Cheshire.

The Roman army had been present in Cheshire for around 20 years before the fortress at Chester was built.  The first legion stationed there was the Second Legion Adiutrix. When they were called away to defend mainland Europe around 87AD, the fortress was occupied by the Twentieth Legion, Valeria Victrix. They rebuilt much of the fortress in stone and their emblem, the running boar, was stamped on the roof tiles used on new buildings.

The first legion stationed there was the Second Legion Adiutrix. When they were called away to defend mainland Europe around 87AD, the fortress was occupied by the Twentieth Legion, Valeria Victrix. They rebuilt much of the fortress in stone and their emblem, the running boar, was stamped on the roof tiles used on new buildings.

Auxiliary Forts

As well as the legion stationed at Chester, there were other soldiers at auxiliary forts at Northwich and Middlewich. Auxiliary forts were built to accommodate between 500 and 1000 men. The soldiers were recruited from the local population of a province so were not Roman citizens and were either infantry or cavalry. Two diplomas found in Middlewich and Malpas were issued to soldiers from cavalry units. They may have been stationed here or settled in Cheshire after retirement.Northwich Fort

The auxiliary fort in Northwich was founded around 70AD and then abandoned for a time before being rebuilt in the 2nd century. In 1969, a rare cavalry helmet was found suggesting there may have been cavalry units in Cheshire in the 1st century AD. A reconstruction of the helmet can be seen on display in the Northwich Information Centre, Weaver Square, Northwich, together with a small collection of other Roman finds from Northwich. The original iron helmet was found in the Castle area of Northwich and is a rare type of helmet worn by a Roman auxiliary soldier. It dates to around AD 100. A stylized hair pattern is visible on the crown. The helmet would have been worn by one of the cavalry troops stationed at the Roman fort in Northwich.

being rebuilt in the 2nd century. In 1969, a rare cavalry helmet was found suggesting there may have been cavalry units in Cheshire in the 1st century AD. A reconstruction of the helmet can be seen on display in the Northwich Information Centre, Weaver Square, Northwich, together with a small collection of other Roman finds from Northwich. The original iron helmet was found in the Castle area of Northwich and is a rare type of helmet worn by a Roman auxiliary soldier. It dates to around AD 100. A stylized hair pattern is visible on the crown. The helmet would have been worn by one of the cavalry troops stationed at the Roman fort in Northwich.

Middlewich Fort

Geophysical survey work and excavation have confirmed that there was an auxiliary fort at Middlewich on Harbutt's Field. Five Roman roads (from Chester, Warrington, Whitchurch, Buxton and Chesterton) meet at Middlewich where the Rivers Dane and Croco have natural fords. The fort was built as a permanent structure around 70AD and occupied until 130AD. The forces stationed here are likely to have been in control of the salt working settlement on either side of King Street, the Roman road from Warrington to Chesterton.Castra Deva

Chester, or Castra Deva, which means "the military camp on the River Dee", was home to the Twentieth Legion (Valeria Victrix) for about 200 years. Chester's geographical position made it one of the finest strategic outposts of the Roman Empire. The Romans invaded Britain in AD 43, but it was another 30 years before they reached the north-west of the country. The Roman army arrived in Chester sometime between AD 71 and 79 and began to build a great fortress on a headland overlooking the River Dee. The precise date that construction of the fortress began has been much debated but the discovery of inscribed lead ingots cast in AD 74 and lead water pipes manufactured during the first half of AD 79 have been associated with construction of the legionary fortress.Chester's strategic importance

The local topography and surrounding landscape has changed considerably since the Roman Army arrived in Chester. It is therefore difficult to now appreciate many of the factors that caused the Roman Army to select Chester as the location for a legionary fortress. The Course of the River Dee was undoubtedly the most influential. As it approaches Chester from the south the River Dee swings sharply to the west cutting through the low ridge of sandstone, forming a narrow gorge before opening out again into the bowl-shaped area now occupied by the Roodee racecourse. The narrowness of the gorge and its rock banks facilitated the bridging of the river while the broad expanse of the Roodee afforded a natural harbour. The fortress was sited on the north side of the river some distance back from the steep drop down but still in a position where it was able to command the crossing.Legion XX arrives in Chester

Legion II had to be withdrawn from Britain in the late AD80's to reinforce Roman armies on the Danube. The conquest of Scotland was now almost complete, but after the withdrawal of so many troops it was no longer possible to hold what had been won. The historian Tacitus describes the Romans' frustration at the time; "perdomita Britannia et statim missa" - "Britain was completely conquered, then straightaway let slip". The remaining Roman forces in Britain were pulled back from Scotland. Legion XX Valeria Victrix, which had been based at Inchtuthil on the River Tay in Scotland, was brought south to occupy the now empty fortress at Chester, where it was to remain for at least 150 years.Soldiers

We know many of the names of the soldiers who lived in Cheshire thanks to two very important sources of information, tombstones and military diplomas. The Latin text on these artefacts shows that soldiers in Cheshire were recruited across the Empire, from Spain, France, Italy and the Danube frontier. The tombstone to the right is of Caecilius Avitus, an Optio of the 20th Legion. The optio was an administrator and was second in command to a centurion. His duties included some of the book-keeping for the century. He is dressed in a heavy cloak (sagum), and wears a legionary's sword at his side. In his right hand he carries a staff of office, while in his left hand he holds a writing tablet. The inscription reads:

The Latin text on these artefacts shows that soldiers in Cheshire were recruited across the Empire, from Spain, France, Italy and the Danube frontier. The tombstone to the right is of Caecilius Avitus, an Optio of the 20th Legion. The optio was an administrator and was second in command to a centurion. His duties included some of the book-keeping for the century. He is dressed in a heavy cloak (sagum), and wears a legionary's sword at his side. In his right hand he carries a staff of office, while in his left hand he holds a writing tablet. The inscription reads:D :M

CAECILIVS:AVIT

VS:EMER:AVG

OPTIO:LEG:XX

V:V:STP:XV:VIX

AN:XXXIIII

H:F:C:

Expanded this reads:

Dis Manibus Caecilius Avitus Emerita Augusta optio Legionis XX Valeriae Victricic stipendiorum XV vixit annos XXXIIII heres faciendum curavit.

Which means:

"To the spirits of the departed, Caecilius Avitus of Emerita Augustus, an optio of the Twentieth Legion Valeria Victrix, served 15 years and lived for 34 years. His heir had this stone made."

Emerita Augusta is now Merida in south-western Spain. This stone was originally painted white with details highlighted in other colours. A replica depicting how it would have looked along with the original tombstone can be seen at the Grosvenor museum in Chester.

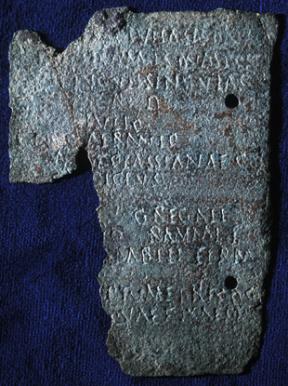

Military diplomas are a rare find in Britain yet two have been found in Cheshire, in Middlewich and  Malpas. Diplomas were issued to auxiliary soldiers on completion of 25 years service. They granted Roman citizenship to the holder. If a soldier was married, the diploma legalised this and any children were granted citizenship. Before 197AD soldiers were forbidden to marry. However many did have families who lived outside the forts in civilian settlements.

Malpas. Diplomas were issued to auxiliary soldiers on completion of 25 years service. They granted Roman citizenship to the holder. If a soldier was married, the diploma legalised this and any children were granted citizenship. Before 197AD soldiers were forbidden to marry. However many did have families who lived outside the forts in civilian settlements.

Made of two hinged rectangular bronze plates inscribed in Latin, they were personal copies of decrees displayed in Rome. The inner faces of the tablets were inscribed with details of his service and the privileges now granted him as a retiring soldier.

The fragment of a Roman military bronze certificate on the left was found in 1939 and is known as the Middlewich Diploma. It was issued by Emperor Trajan in 105 AD to a soldier on the completion of 25 years service. The soldier was from a cavalry unit known as 'ala classiana Romanorum' but the soldier's name is not known.

Just 13 diplomas have been found in Britain. The most complete diploma was discovered in Malpas, Cheshire in 1821. It is now housed in the British museum but a replica can be seen at Chester's Grosvenor museum. The diploma is made out to horsemen and foot soldiers serving under Lucius Neratius Marcellus, Governor of Britain. It is dated 19th January AD 104, during the reign of Trajan. The outside of the bronze plates are inscribed with the names of 7 witnesses.

Though far away from home, soldiers would still have enjoyed the things they were used to. Fine pottery, wine and olive oil were some of the goods transported to every corner of the Empire. Evidence of these products has been found at Roman settlements across Cheshire, whether fort or farm, showing that they were also available to the local population.

Legionary equipment

The Roman Empire lasted for many centuries, and during that time the appearance of the legionary's armour and weapons changed considerably. For example, at the time of the building of Chester (AD 75-80)he would have worn armour made out of iron bands or hoops - called lorica segmentata in latin. This is the type of armour which you will usually see Roman soldiers wearing when they appear in films or books today.

weapons changed considerably. For example, at the time of the building of Chester (AD 75-80)he would have worn armour made out of iron bands or hoops - called lorica segmentata in latin. This is the type of armour which you will usually see Roman soldiers wearing when they appear in films or books today.

Within 150 years new sorts of armour had come into use. These were scale armour, made from thousands of tiny metal plates sewn onto a strong cloth backing (lorica squamata); and chain mail, made out of interlocking iron rings (lorica hamata).

Body Armour

The legionary had to move about easily, not only in battle but at other times too. Even when he was doing engineering work it might be necessary for him to wear his armour in case there was an ambush. The lorica squamata was designed to give as much protection as possible in these circumstances. Modern replicas show that the lorica is surprisingly comfortable, and it is very easy to bend or move about when wearing it.The lorica segmentata worn by the Roman soldier to the right is an early type from the 1st century AD. The shoulder hinges and other fastenings on the design are known to have given a lot of trouble in service, because broken parts often turn up on excavations. Later versions of the lorica had simpler and stronger fastenings.

Shield

The legionary was well protected by a shield which was up to 1.25m (4ft) high. It was made from thin layers of wood glued together, then covered with linen. The edges and central boss were made of metal. Various designs and colours were used on the front face of the shield so that different units could easily be recognised. If a unit of legionaries was attacked by arrows or spears, some of the soldiers would make a wall out of their shields while others locked their shields together over their heads. This formation was called the testudo ("tortoise").Belt and Dagger

A broad leather belt decorated with metal plates was worn round the waist. It carried an apron of studded leather strips which protected the upper thighs. The dagger was attached to the belt and worn on the left hip. It was used as a tool as well as a weapon. The photo on the left shows a complete dagger and scabbard found on different sites in Chester. The dagger was recovered in an excavation at Abbey Green during 1975-8. The sheath of a dagger was found during an earlier excavation between 1924 and 1928 at the nearby Deanery Field which is known to have been the site of a legionary barracks. The dagger and scabbard are now on display at the Grosvenor museum in Chester.

It carried an apron of studded leather strips which protected the upper thighs. The dagger was attached to the belt and worn on the left hip. It was used as a tool as well as a weapon. The photo on the left shows a complete dagger and scabbard found on different sites in Chester. The dagger was recovered in an excavation at Abbey Green during 1975-8. The sheath of a dagger was found during an earlier excavation between 1924 and 1928 at the nearby Deanery Field which is known to have been the site of a legionary barracks. The dagger and scabbard are now on display at the Grosvenor museum in Chester.

Sword

The sword was short with a broad double-edged blade. It was designed for stabbing, not slashing. Note that the legionary wore his sword and its scabbard on his right, the same side as his sword arm.Spear

The point of the legionary's spear, the pilum, was hardened and very sharp. On the other hand the long shank, from the point to the wooden shaft, was deliberately made soft so that it would bend easily. Once the spear had hit its target in battle it would buckle or twist, and so it was difficult for an enemy to pull out or throw it back.Boots

Roman boots had open tops like modern day sandals, but underneath they had thick soles with lots of iron studs (hobnails). The studs helped to give the soldier extra grip on slippery surfaces, and also made the boots last longer. In cold weather socks were worn.Helmet

The helmet was designed for protection rather than comfort. An older soldier could be recognised out of uniform by the scar under his chin where his helmet's straps had rubbed. There was a strengthening rib across the brow, and large cheek pieces on either side. These protected the face against a slashing sword cut. The ears and the back of the neck were also well protected.Other equipment

On the march the legionary wore all of his armour, except for his helmet, and carried his own weapons. He had many other things to carry as well. There were various tools, like the dolabra - half pick, half axe; there was a wicker basket, for carrying surf or soil when the legionaries were building their overnight camp; and a set of cooking utensils including a patera - a bronze saucepan. All this extra equipment weighed over 25kg (50lbs).Legionary Barracks

Two legionary barracks were excavated at the Deanery Field in Chester during the 1920's. The Deanery field is now a large open space to the north of the Cathedral.Each century of about 80 men lived in a barrack block constructed to a standard plan. Legionary barracks were usually built in sets of six, each set housing one cohort, i.e. 480 men. They were half-timbered, with two or three courses of sandstone masonry to raise the woodwork clear of the ground.

The century was divided up into units of 8 men who lived together. Each group, known as a contubernium (which means 'tent party'), lived in two rooms. The front room, which faced into the verandah, was a general storeroom where the men's equipment was kept. The back room was used for sleeping and eating, and was usually fitted with a fireplace.

The centurion lived in much more luxurious rooms at the end of the barrack block. His quarters would have had painted plaster walls and concrete floors.

Legion XX Headquarters

The principia (headquarters building) was the most important and impressive building in the fortress. Inside it most of the paperwork and day-to-day running of the legion was carried out. A large courtyard was surrounded by offices and stores. Behind the courtyard was a great hall called the basilica. It had aisles and a nave, and would have looked very much like a large church. The legionaries could be called together inside for announcements or presentations. The commander or officer in charge stood on a raised platform (tribunal )at one end of the hall.

At the back of the basilica were yet more offices, and in the middle of them was the regimental shrine (aedes). This room was at the very heart of the fortress and was treated with great reverence by the soldiers. In it was kept the golden eagle which was the special standard of the legion. There were also the various other standards and banners of the legion, and busts of the reigning emperor and his family. Under the floor of the aedes was a vault in which the fortress' pay chest was kept. This small room, known as the aerarium, was also used as a bank for the soldiers' savings.

Civilians

The local population lived outside the military settlements and in the country. Sometimes their names survive in inscriptions.Some inscriptions record names as a sign of ownership. One of several lead salt-pans found in Northwich was inscribed with the name VELVVI which is a Romanised version of the Celtic name Veluvius. And a wooden barrel from Middlewich has the inscription "LEV" clearly marked on it.

Civilians were not always local. Military communities attracted settlers from across the empire. Traders in particular were drawn to these new markets. A tombstone records the Greek names of Flavius Callimorphus and his son, Serapion. Two rare inscriptions in Greek from Chester record dedications by doctors Hermogenes and Antiochus.

Pre-conquest

The Twentieth Legion was one of four legions involved in the conquest of Britain under the command of Aulus Plautius. He had been governor of the Roman province of Pannonia which was in the south-east of modern day Europe. Legion IX 'Hispana' was based in Pannonia and Plautius brought it with him along with Legion II 'Augusta' from Strasbourg, Legion XIV 'Gemina' from Mainz, and Legion XX (the Twentieth) which was based in Neuss, now modern day Germany. The Twentieth did not yet have its title 'Valeria Victrix', which was to be awarded after the suppression of the rebellion under Boudica in AD 60 or 61. It is difficult to say how many men were actually involved in the invasion force as the legions may have left some men behind in the original bases. However, it has often been estimated that each expeditionary legion consisted of around 5000 fighting troops with a similar number of auxiliary troops giving a total invasion force of approximately 40,000 troops.

The Twentieth Legion was one of four legions involved in the conquest of Britain under the command of Aulus Plautius. He had been governor of the Roman province of Pannonia which was in the south-east of modern day Europe. Legion IX 'Hispana' was based in Pannonia and Plautius brought it with him along with Legion II 'Augusta' from Strasbourg, Legion XIV 'Gemina' from Mainz, and Legion XX (the Twentieth) which was based in Neuss, now modern day Germany. The Twentieth did not yet have its title 'Valeria Victrix', which was to be awarded after the suppression of the rebellion under Boudica in AD 60 or 61. It is difficult to say how many men were actually involved in the invasion force as the legions may have left some men behind in the original bases. However, it has often been estimated that each expeditionary legion consisted of around 5000 fighting troops with a similar number of auxiliary troops giving a total invasion force of approximately 40,000 troops.

Invasion and Conquest

Following the invasion, the Twentieth legion, or at least part of it, was at Colchester for a few years where its role in keeping the peace and controlling the natives would have been of prime importance at the early stage of the conquest. It is not certain precisely where in Colchester the fort for the Twentieth legion was located but remains of a Roman fort have been found on the same site where Cunobelinus, king of south eastern Britain had previously had his own dwellings. It would certainly have made an unequivocal statement to the local population by the conquering legion, by placing a fort directly where their king had previously held court.

the fort for the Twentieth legion was located but remains of a Roman fort have been found on the same site where Cunobelinus, king of south eastern Britain had previously had his own dwellings. It would certainly have made an unequivocal statement to the local population by the conquering legion, by placing a fort directly where their king had previously held court.

Between AD 47 and 52 Osturius Scapula took command of the legions in Britain and Plautius returned to Rome. After campaigns by Osturius against the Deceangli in Wales and the Brigantes of the north, he brought the Twentieth legion out of Colchester to fight against the Silures of south Wales. The campaign against the Silures was a difficult one and a legionary base was required to keep them in order. It is likely that the Twentieth legion was placed for a short period in the legionary fortress at Kingsholm, near Gloucester whilst campaigning against the Silures.

Marcus Trebellius Maximus took over as governor of Britain in 63 AD to what was a relatively quiet period with no significant military action during his term of office. As such, there was limited need for the four legions. In 66 or 67 AD one of them, Legion XIV, now with the title of Martia Victrix for its part in the defeat of Boudica, was withdrawn by Nero, along with eight auxiliary cohorts of Batavians. For a short time the legionary complement of Britain comprised II Augusta, IX Hispana, and XX Valeria Victrix.

Trebellius may have been responsible for moving the Twentieth legion out of Usk to resettle in Gloucester, a somewhat retrograde movement since it had moved from Kingsholm near Gloucester only a few years before. Alternatively, some researchers think that it may have gone to Wroxeter when Legion XIV was recalled by Nero, but for the Twentieth that move probably occurred some years later. The II Augusta and IX Hispana legions remained respectively at Exeter and Lincoln. The soldiers were no doubt kept busy on patrols, carrying out police work, securing supplies, perhaps even helping to rebuild the towns, but they were not given the opportunity for military action. Inactivity for prolonged periods was not good for any army morale, and boredom and discontent set in. The Twentieth legion had perhaps more cause for complaint than the others, because it had moved around much more frequently from one base to another. The legionary legate, Roscius Coelius, took it upon himself to be spokesman for his own Twentieth legion and the other legions and rapidly became the leader of the restless troops. Trebellius lost all authority with the army, which had now sided with Coelius, and he fled to the protection of Vitellius in Germania. Coelius and his fellow legates briefly ruled the province until Vitellius, now emperor, sent Marcus Vettius Bolanus to be the new governor in late AD 69. In AD 71 Vespasian became emperor and he recalled Coelius, whose treacherous behaviour had been made known to him, and replaced him as commander of the Twentieth with Gnaeus Julius Agricola.

Aulus Plautius commanded the Roman invasion force of 4 legions in 43 AD

Aulus Plautius commanded the Roman invasion force of 4 legions in 43 AD

After Vespasian had established himself as emperor, Agricola was appointed to the command of the Legio XX Valeria Victrix, stationed in Britain, in place of Marcus Roscius Coelius, who had stirred up a mutiny against the governor, Marcus Vettius Bolanus.

After Vespasian had established himself as emperor, Agricola was appointed to the command of the Legio XX Valeria Victrix, stationed in Britain, in place of Marcus Roscius Coelius, who had stirred up a mutiny against the governor, Marcus Vettius Bolanus.  Replica of Caecilius Avitus' tombstone, an Optio of the 20th Legion. The replica depicts how the tombstone would have originally looked.

Replica of Caecilius Avitus' tombstone, an Optio of the 20th Legion. The replica depicts how the tombstone would have originally looked.