Chester's Rows

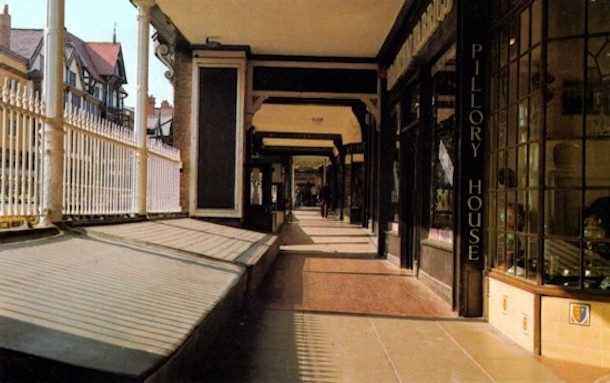

Perhaps one of the

most distinctive architectural features of Chester are the Rows. These

two-tiered medieval galleries are now home to some of the best shops in

the city.

The Rows are a unique system of covered walkways with shops and

commercial properties on two levels. They are open to the street on one

side and the levels can be reached from stairs at ground level. Records show that the Rows have existed at least since the late 13th

century. How they came to be built is not known for sure, but a

devastating fire in 1278 and subsequent attempts at town planning could

account for their origins. However, archaeological

excavations have so far found no evidence for this fire and there is no

real evidence that re-building was deliberately 'planned' to include a

Row system. The first documentary references to Rows, relate to the area

around St. Peter's Church in the commercial heart of the city. By the

1290s, the area on the east side of Northgate Street was known as

Ironmonger's Row and houses with undercrofts are recorded. These early

Row buildings probably had an elevated gallery, but were not yet part of

a continuous system. Access to Row level would have been by many

different flights of steps. However, during the 14th century galleries

were gradually linked to form continuous walkways, possibly through the

co-operation of adjacent property owners who needed to make their

premises more accessible. The splendid black and white half-timbered buildings of The Rows which are

now visible may have existed since Medieval times but have been rebuilt and renovated

over time and a closer look reveals that most of the current buildings

are in fact of Victorian or even Edwardian design. A Scandinavian link has also been suggested, as there was a known

Scandinavian presence in the city in the 9th and 11th centuries. The Rows are found on four main streets in the city - Bridge Street,

Watergate Street, Eastgate Street and part of Northgate Street. During

the Civil War, Chester suffered a disastrous siege from November 1644

until February 1646, when it was starved into surrender. The city was

very badly damaged and the economy was in tatters. Rebuilding took many

years, continuing well into the 1660s. Timber was still the favoured

material, although brick was now in use in other parts of Cheshire.

However, towards the end of the 17th century, Chester's prosperity

revived and the city became a fashionable social centre. Landed families

began to rebuild their old town houses in the latest classical styles.

Wherever possible they sought to get rid of the Row, which was both

architecturally unfashionable and an intrusion on their privacy. During

the late 17th century and 18th centuries, significant sections of the

ancient Rows system was lost through enclosure or rebuilding. The earliest recorded enclosure of a Row was during the Civil War in 1643, when Sir Richard Grosvenor

petitioned the Assembly to enclose the Row of his town house in Lower

Bridge Street (now the Falcon), in order to enlarge the building. As a

leading Royalist commander, garrisoned at Chester Castle, his request

was granted and the Row walkway was enclosed to form a new room in the

front of the house. The stone columns which once supported the upper

floor and the original shop front at Row level, can still be seen in the

Falcon bar. The grant to Richard Grosvenor set a precedent which was to lead to the loss of almost all

the Rows in Lower Bridge Street. Because of the turmoil of Civil War, it

was not until 1668 that the next permission to enclose was sought and

granted. Once a section of Row has been lost, householders were able to

claim that it was now useless as a public walkway. In 1676, Lady Mary

Calvely petitioned to enclose a Row so that she could build an entirely

new mansion - Bridge House (now Oddfellows Hall) was envisaged to be

"a grace and ornament to the city". In 1699, the lawyer John

Mather also gained permission to build a major new house, resulting in

the loss of the Row at 51 Lower Bridge Street. Not all property owners

had the wealth to completely rebuild, many simply re-fronted their

houses, absorbing the Row as an additional room. The Row of Tudor House,

enclosed by Roger Ormes in 1728, still survives within the building. The Rows of Lower Bridge Street were sacrificed to architectural fashion because they had become

predominantly domestic rather than commercial. Elsewhere, in the heart

of the city, the Rows were still thriving places of trade and the

Assembly exerted control by refusing permissions to enclose. Sir George Booth who rebuilt two medieval houses in Watergate

Street in 1700, was obliged to keep the Row walkway, ingeniously

creating the best classical mansion in the Rows. However, Row enclosure

can be traced in all four main streets, with the sections of Row

furthest from the commercial heart of the city generally being lost. The rows have secondary names which derive from the traders who carried on their

business there (Shoemakers´ Row, Ironmongers´ Row, etc). Today they

mostly house a variety of small shops, bars and restaurants, although

there are still some private houses on the Rows. In some places the Rows

have been "enclosed", that is the Row has been blocked-off at

both sides and the space has been incorporated into a building. Often,

as in Lower Bridge Street, the internal layout of these buildings

reflect the fact that the Row once passed through them - a particular

example is the Old Kings Head another is the Falcon. Several of the shops at street level on the Rows have medieval stone

cellars or crypts. Although some of them have been radically altered, a

few remain and are worth a visit.