St. John's Church

The Church of St. John the Baptist is sited beside the Roman amphitheatre, just outside the city walls and overlooking the River Dee. St John's is Chester's oldest Church and has been a site of Christian Worship for nearly thirteen centuries. The present building has stood for more than 900 years.  The Church was partially rebuilt in AD 1075 by Bishop Peter of Mercia and raised to Cathedral Status until the 13th Century when it became a Collegiate Church. St. John's then became a Parish Church in the 16th Century, following the Reformation.

The Church was partially rebuilt in AD 1075 by Bishop Peter of Mercia and raised to Cathedral Status until the 13th Century when it became a Collegiate Church. St. John's then became a Parish Church in the 16th Century, following the Reformation.

The Saxon Period

The ancient Church of John's was founded by the Saxon King Aethelred of Mercia in AD 689. It was later enlarged in AD 907 by Aethelreda, the daughter of King Alfred the Great and her husband Aethelred. At that time Foregate Street will have been a mere track through the forest, outside the ancient city walls.

According to legend: "King Ethelred, minding to build a church, was told that where he should see a white hind, there he should build a church, which hind he saw in the place that S. John's now standeth".

Another legend says King Edgar spent time at St. John's in AD 973 to receive homage of the sub-kings of England Scotland and Wales. Legend has it that King Edgar the Peaceful was crowned in Bath, in 972, and was then rowed up the river Dee by eight vassal Kings from North-western Britain, as a token of their submission, from Chester Castle to the church of St. John's where he took oaths of obedience. This story is depicted in the stained glass West window, over the main entrance of St. John's.

1066 - King Harold escapes to Chester!

The Polychronicon by Ranulf Higden, a Benedictine Monk of the monastery of St. Werburgh in Chester, refers to King Harold fleeing to Chester after being defeated at the Battle of Hastings.

Ranulf Higden (c1280 - 12th March 1364) suggests that Harold did not actually die on the battlefield at Hastings: "Gerald of Wales tells in his history how Harold had many wounds, lost his eye to an arrow, and escaped to Chester where he lived as a hermit in the chapel of St. James near St. John's Church. This episode is well known in the City, and Alredus Ryvallense in the 26th chapter of his 'Life of St. Edward' said that Harold dies miserably and in a state of penitence"

When it became known that King Harold was dead, the Earls of Mercia and Northumberland, Edwin and Morkar who had withdrawn themselves from Harold to take up better positions in the battle with the Normans, came to London. They sent their sister Algitha, Harold's wife, to the City of Chester with Aldred Archbishop of York, and men from London who wished to make Edgar Adyling King and to fight for him.

But the fear of William caused them to withdraw from this plan. All these noblemen now came to William and pledged their loyalty to him and gave his assurances.

When William came to London he was crowned King, as William I, at Westminster Abbey by Aldred Archbishop of York (for Stigand of Canterbury declined) on Christmas day which fell on a Monday that year. But he returned to Normandy during the following lent and left his brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, to look after England. He took with him English Noblemen - Earls Edwin and Morkar and Edgar Adyling, and notably Stigband Archbishop of Canterbury, who went reluctantly. The King pretended that he was honouring the Archbishop, but it was in case he should stir up treason in England during the King's absence."

It is recorded in "Vale Royal" that after receiving many wounds at the Battle of Hastings (1066) King Harold fled to Chester and lived for many years in the anchorite cell below St. John's (the building, by what was a bowling green, between St. John's and the river Dee).

The Norman Period

Under Norman rule, it was ordered that all Bishops should reside in the most important cities. As a result, in 1075, Bishop Peter of Mercia transferred his Ministry from Lichfield to Chester. He started the building of his cathedral, St. John's, on the ancient site of the Saxon church, with stone being taken from a quarry between the church and the river (where the site of a disused bowling green can now be found). The design was a large cruciform cathedral church with Nave, Chancel, Choir and Transepts.

Under Norman rule, it was ordered that all Bishops should reside in the most important cities. As a result, in 1075, Bishop Peter of Mercia transferred his Ministry from Lichfield to Chester. He started the building of his cathedral, St. John's, on the ancient site of the Saxon church, with stone being taken from a quarry between the church and the river (where the site of a disused bowling green can now be found). The design was a large cruciform cathedral church with Nave, Chancel, Choir and Transepts.

Bishop Peter lived to see 10 years of the building work, during which time the Norman builders completed the lower part of the Nave, the main arches over the crossing, the two transepts (now gone), the arches going from the present sanctuary into the ruined chancel and altar area outside the east end and the two arches that went the other way to the former tower and the great west door. What was once a long majestic sweep of Norman arches is now severely cut short by the east and west walls.

Bishop Peter died in 1085 and was buried in the original choir, now in the ruins outside the church. His successor moved his ministry to Coventry, in 1102, and building work stopped, From then St. John's was only occasionally used as the cathedral of West Mercia and remained a partially built roofless ruin for nearly 100 years.

16th Century

In 1535 an Act was passed by Henry VIII ordering the Dissolution of all the monasteries and was followed by  the Suppression Act in 1545. The Commissioners sacked the College of St. John's and took all property and silver for the Crown. The Choir and Chantry Chapel were pulled down leaving only the Nave standing.

the Suppression Act in 1545. The Commissioners sacked the College of St. John's and took all property and silver for the Crown. The Choir and Chantry Chapel were pulled down leaving only the Nave standing.

After the suppression of the College, St. John's fell into disrepair and in 1581 the parishioners petitioned Queen Elizabeth to grant them the fabric of the Church. It is said that the Queen's agreement was conditional on the lead being taken by the Crown to help in the fight against the Spanish.

The people of St. John's, using the stonework from ruins, built up the walls at the East and West ends of the Nave and formed the Church as it is today.

The Civil War

During the English Civil War Chester was loyal to the King, but much of Cheshire and south Lancashire were on the Parliamentary side.  St. John's, being outside the City walls, fell to the Parliamentary troops in September 1645. They placed canons on St. John's tower to bombard the City. The siege continued until February 1646 when the walls were breached and the City surrendered.

St. John's, being outside the City walls, fell to the Parliamentary troops in September 1645. They placed canons on St. John's tower to bombard the City. The siege continued until February 1646 when the walls were breached and the City surrendered.

St. John's was left a battered wreck, with the interior destroyed by the soldiers who had used it as a Garrison. All the remaining silver in the Church was taken except one silver chalice, which was hidden. A Baptismal Font was thrown out of the Church by the Parliamentary troops but was later found and returned to the Church in 1661.

Late 17th Century & 18th Century

The Warburton memorial in the Lady Chapel was begun in 1693 on Lady Warburton's death by the sculptor Edward Pierce, although he died before it could be completed. He did much of his work for Sir Christopher Wren (the Architect of St. Paul's Cathedral, London) who was his tutor. This memorial is unique, being his only stone memorial, and has served as a model design for other copiers.

Galleries (balconies) were built between the Norman pillars on both sides of the Nave, and a two deck pulpit constructed under the Chancel arch (across the end of the Nave by the pulpit) in the 17th or 18th century.

Seats in church have not always been free! From the 17th century people were allocated seats in church only if they paid pew rent. Pew rent stopped at the end of the 18th century and seating in church became free.

St. John's houses one of the largest collections of painted 17th century wooden memorial panels in Cheshire. Most were painted by four generations of the Home family (all called Randle), whose own memorial is in St. Mary's church, Handbridge. The panel in the Lady Chapel lists the names of former mayors of Chester who lived in the Parish. The list includes the Earl of Grosvenor, Mayor in 1807, and who lived in a house situated over the old Chapter house next to the church. The Grosvenor family became the Patrons of St. John's in 1810.

19th Century

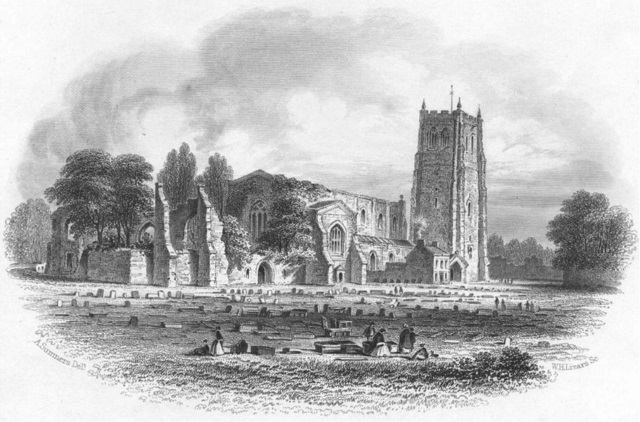

The above view of St. John's shows the full extent of the church in the early 19th century. Many changes have taken place since then and the church looks very different today. The church was dominated by the great North West tower which collapsed at 10pm on Maundy Thursday 1881. Earlier the same day a builder inspected the tower as its condition had given cause for concerns for many years. He warned the Church Wardens and the Vicar that nobody should be allowed to go through the porch as the tower was in danger of falling. That same evening the whole of the North East face of the tower fell, demolishing the old porch and part of the North Aisle. Only the ruined stump now survives, as it was not practical to rebuild the old tower. It was replaced by a clock tower to house the bells at the eastern end, designed by the noted Chester architect John Douglas.

The organ used at Queen Victoria's Coronation, on 28th June 1838, was purchased from Westminster Abbey for installation at St. John's. It was brought to Chester by canal barge and reassembled in the West Gallery and used for the first time on 28th October, 1838 - just 4 months later!

The organ used at Queen Victoria's Coronation, on 28th June 1838, was purchased from Westminster Abbey for installation at St. John's. It was brought to Chester by canal barge and reassembled in the West Gallery and used for the first time on 28th October, 1838 - just 4 months later!

The East window (behind the main altar) was glazed by Clayton and Bell in 1863-77. It depicts the wedding in Cana of Galilee and was put up to celebrate the wedding of the then Prince of Wales, who later became King Edward VII

The ruined eastern chapels, cut off from the main body of the church in 1581, were enclosed behind a high wall. This was removed in 1871, when the present retaining wall and buildings were built.

Between the entrance porch and the remains of the north transept was a small house, built by a Mr Orange in 1756. It was demolished in 1855. There was another house inside the ruins. In the 18th century this was owned by the mother of the author Thomas de Quincey. Only the small chimney stack can be seen in the above view.

The northern graveyard was closed and leveled in 1876 in the interests of “public decency and public safety”. No further coffins were laid to rest in or around St. John's. A register was made in 1912 when the ground was leveled, listing over 1800 gravestones and monuments.

The northern graveyard was closed and leveled in 1876 in the interests of “public decency and public safety”. No further coffins were laid to rest in or around St. John's. A register was made in 1912 when the ground was leveled, listing over 1800 gravestones and monuments.

20th Century

The magnificent processional cross, which is used today in services, was found in an antique shop. It's made of 16th Century Spanish Silver and is thought to be part of the plunder brought back by Wellington's troops after the Peninsular War.

The Lady Chapel now combines the old south transept and the only remaining bay of the original choir. The chapel was formed in 1928 when the Jacobean gates were moved to their present location and an oak screen was built behind the choir stalls.

In 1946 electric lighting was finally installed to replace the gas lights.

North West Tower

Pictured above is the base of the great North West Tower of St. John's which collapsed in 1881. Originally, it was nearly three times as high and was a major local landmark.

The Norman church was planned in a cruciform shape with a central tower and two towers at the west end. The south west tower was probably never built. The north west tower is said to have been rebuilt after sections fell down in 1572 destroying the western bay of the nave.

The tower was richly decorated and with a keen eye you can still see remains of the patterned tracery bands and one of the carved niches which held many statues. The figure of St. Giles which originally stood over the west window is now above the entrance porch.

On Good Friday, 15th April 1881, the North West Tower and belfry collapsed, destroying the fine Early English entrance porch.  The crash was heard all over Chester. The porch was rebuilt in replica and a new clock tower to house the bells was constructed at the east end of the church.

The crash was heard all over Chester. The porch was rebuilt in replica and a new clock tower to house the bells was constructed at the east end of the church.

During the Civil War in 1645, St. John's was captured by the parliamentary forces who besieged Royalist Chester. A platform for cannon was built inside the tower and the city was badly damaged by bombardment from the church. On the 24th September 1645, King Charles I narrowly escaped being hit by musket fire from St. John's as he stood on the Cathedral tower to watch the defeat of his army at the battle of Rowton Moor.

The Eastern Ruins

The eastern ruins are part of the original east end of St. John's Church. They include part of the Norman chancel, the 14th century Lady Chapel and two medieval side chapels.

The eastern ruins are part of the original east end of St. John's Church. They include part of the Norman chancel, the 14th century Lady Chapel and two medieval side chapels.

St. John's was Chester's first Cathedral. In 1075, Bishop Peter of Lichfield moved the seat of his diocese to Chester and began to build a cathedral church. In 1102 the see was moved to Coventry, but St. John's remained an important collegiate church. Bishop Peter died in 1085 and is thought to have been buried in the Choir of the eastern ruins. (insert picture -seal of Peter)

The church took 200 years to build, reaching its most complete form in the early 13th century. It was then more than twice the length of the church today. In the 14th century it was further extended to the east, when three semi-circular Norman apses were replaced by the chapels which are now ruined.

The church took 200 years to build, reaching its most complete form in the early 13th century. It was then more than twice the length of the church today. In the 14th century it was further extended to the east, when three semi-circular Norman apses were replaced by the chapels which are now ruined.

After the Dissolution St. John's became a parish church. The eastern chapels and the transepts were abandoned. Unable to maintain such a large building, the parishioners built a new east wall, leaving the ruined east end outside the church.

Regarded as one of the mysteries of Chester, a 13th century coffin bearing the inscription “Dust to Dust” is set high into the walls of the Eastern Ruins. The coffin was found by the Sexton in the 19th century and set into the wall on the Vicar's orders.

South Eastern Chapel

The South Eastern Chapel is one of two medieval chapels built on either side of the Lady Chapel. It replaced a Norman chapel which was probably semi-circular. This is the most complete part of the ruins and the walls survive almost to their full height.

The South Eastern Chapel is one of two medieval chapels built on either side of the Lady Chapel. It replaced a Norman chapel which was probably semi-circular. This is the most complete part of the ruins and the walls survive almost to their full height.

This was a chantry chapel, built in memory of Sir Peter Roter, Lord of Thornton, who in 1349 helped to pay for much needed repairs to the church. The Dean and Chapter built the chapel in gratitude and appointed two priests to says services here.

The chapel has a complex history. As part of the church it would have looked very fine, with a stone vaulted roof. After the demolition of the Choir, the chapel was converted into living accommodation for the minor clergy. If you stand in the chapel and look up, you will see the square holes for the joists of the floors cut into the masonry. A fireplace and chimney can also be seen at the very top in one corner.

The chapel has a complex history. As part of the church it would have looked very fine, with a stone vaulted roof. After the demolition of the Choir, the chapel was converted into living accommodation for the minor clergy. If you stand in the chapel and look up, you will see the square holes for the joists of the floors cut into the masonry. A fireplace and chimney can also be seen at the very top in one corner.

The arch pictured above has been partly blocked up. It once led into the south aisle of the choir. There was another opening to the right, leading into the Lady Chapel. A new entrance has been created to the left by breaking through the base of a window.

The arch pictured above has been partly blocked up. It once led into the south aisle of the choir. There was another opening to the right, leading into the Lady Chapel. A new entrance has been created to the left by breaking through the base of a window.

Set high up in the wall of the chapel can be seen a medieval oak coffin inscribed with the words “Dust to Dust”. It was discovered in the 19th century and set high into the ruins so that it could be seen above the tall wall which once surrounded them.

The Choir

(Insert picture of 'the ancient choir')The ancient Choir of St. John's was cut off from the rest of the chancel when the east wall was built in 1581. Services had been sung and celebrated in the Choir for 450 years.

In the Middle Ages, the Choir was just as impressive as the interior of the church today. Massive round pillars with semi-circular arches above ran down each side, continuing the Norman arcading which can still be seen inside the church. Their position is marked on the ground.

It is possible to still see the base of an original pillar which may have supported one of a pair of towers at the eastern end of the Norman church. Little is known about these towers which may have been demolished in the 14th century.

The High Altar stood beneath the impressive Norman chancel arch. Behind were the Lady Chapel and two side chapels. These were built in medieval times. You can see the differences in style between the round-headed Norman arch and the later Gothic pointed arches on either side. Due to the growth of trees it is now difficult to stand back and view all three arches, but the image below from a postcard mailed in 1917 gives a good perspective.

On both sides of the central chancel arch are stone arches or “blind arcading”. These were part of the Norman decoration. They have been cut through by the remains of two staircases, added in the 16th century, when the Choir was demolished and the chapels were converted to living accommodation. The stairs led to upper floors.

.jpeg)