Chester in the Civil War

Chester supported King Charles during the English Civil War. This was mainly due to the fact that the King's eldest son was Earl of Chester and the influence of the locally important Gamull family. When war broke out local Royalist support became very strong in Chester and when Sir William Brereton, a local Parliamentarian, tried to rally support for the Parliamentarians in the city centre, there was nearly a riot. Sir William left Chester to try and raise support elsewhere, and his town house by the Racecourse called Nunnes Hall was burned to the ground.

Chester supported King Charles during the English Civil War. This was mainly due to the fact that the King's eldest son was Earl of Chester and the influence of the locally important Gamull family. When war broke out local Royalist support became very strong in Chester and when Sir William Brereton, a local Parliamentarian, tried to rally support for the Parliamentarians in the city centre, there was nearly a riot. Sir William left Chester to try and raise support elsewhere, and his town house by the Racecourse called Nunnes Hall was burned to the ground.

Chester was an important trade centre. Its situation as Gateway to  Wales and as a port meant that it was also in an important strategic position which the Parliamentarians would be keen to control. Throughout the war they tried to break through the city's defences but without success. However, from 1644 the Royalist armies were concentrated in the south of England, leaving the north to fend for itself. The knowledge that there would be no military relief for Chester made the Parliamentarians more determined to win the city, thus making a siege situation almost inevitable.

Wales and as a port meant that it was also in an important strategic position which the Parliamentarians would be keen to control. Throughout the war they tried to break through the city's defences but without success. However, from 1644 the Royalist armies were concentrated in the south of England, leaving the north to fend for itself. The knowledge that there would be no military relief for Chester made the Parliamentarians more determined to win the city, thus making a siege situation almost inevitable.

Chester's Defences

The Chester Royalists quickly realised that there was a need for strong city defences against Parliamentarian attacks. The ancient city walls were still standing but were falling down in places and in need of repair. By October 1642, just two months after the start of the war, 300 men were trained and armed with muskets. One month later the city gates were guarded by armed men. The City walls were strengthened and by the spring of 1643 mud outworks had been built as the first line of defence around the north and east of the city. Watchtowers were built upon these out-works, to give early warning of an attack. No outworks were needed on to the south and west of the city because the River Dee formed a natural barrier against invaders. The fortified City Walls became the final line of defence, with deep ditches which soon filled with foul stagnant water, dug around them as a further obstacle to attack.

Although most people lived within the City Walls at that time, there were houses in what are now Foregate Street, Northgate Street, Boughton and Handbridge. After a surprise attack on the eastern suburbs which caused the Mayor to flee from his home in Foregate Street, the Royalists decided to burn all the suburbs down. This improved their view of Parliamentarian movements, and stopped the enemy from using the buildings for themselves. This was obviously a drastic move, especially for the people who lived in the suburbs, but in the time of civil war great sacrifices were made. Initially all the Royalist soldiers were volunteers, but in June 1643 conscription was introduced and all men in Chester aged 16-60 were required to fight to defend the city.

The fortification and defence of Chester was a very expensive exercise. Taxes had to be levied on the Chester residents to pay the garrison of soldiers stationed there, and also for the building work involved in the defences. However, trade was reduced by the war, and people found it difficult to pay the taxes. In the end the silver treasures of the city had to be melted down. These were turned into coins to pay for the defence of Chester.

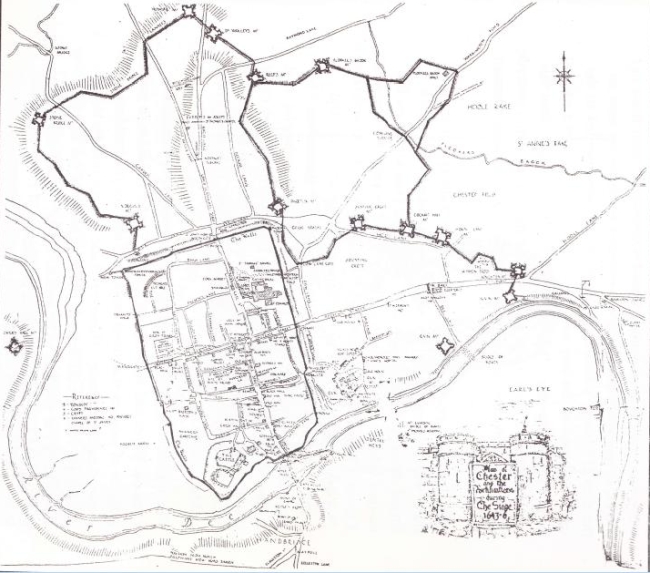

The above plan of Chester shows fortifications to the north and east of the city during the civil war. The River Dee offers a natural defence to the south and east of the city.

The above plan of Chester shows fortifications to the north and east of the city during the civil war. The River Dee offers a natural defence to the south and east of the city.

The Parliamentarian Positions

Parliamentarian attacks on Chester were led by Sir William Brereton. He was a local man who had nearly caused a riot by trying to gain support for the Parliamentary cause within the City Walls. The Parliamentary soldiers were based at camps around the city. The camps were formed at Tarvin, Christleton, Hoole, and Puddington in an attempt to blockade Chester.

The Royalists had spent a great deal of time and money building mud outworks to defend the city. However, the Parliamentarians were able to break through these defences, and set up gun emplacements very close to the City Walls. These were situated at Morgan's Mount, the Water Tower, Brewer's Hall (opposite the Roodee), Handbridge, The Groves and the Eastgate. Once they had broken through the mud outworks, the Parliamentarians were able to use them for their own benefit. Several of the gun emplacements were put on the site of former Royalist defences.

The Parliamentarians also built a bridge of boats across the river near Dee Lane. This supply line across the Dee annoyed the Royalists who tried to destroy it by floating burning boats towards the bridge. This attempt failed because of the Parliamentarian defences, and the action of the tide. the bridge of boats remained until icy conditions during the winter caused it to break up.

The Parliamentarian Attacks on Chester

Parliamentarian attacks on Chester began in July 1643. The first attack was a total failure. The only two Royalist casualties were two youths who paraded along the City Walls, taunting the enemy to shoot them. Not wishing to disappoint the two young Cavaliers, the Parliamentarians promptly shot and killed them both.

Further attacks took place regularly, but in March and May 1645 Sir William Brereton was forced to lift the siege as Royalist reinforcements approached. However, the reinforcements were diverted, and the siege was soon renewed.

The Parliamentary gun emplacements were so close to the City Walls that the cannon balls were able to damage both the Walls themselves, and the buildings within them. Many civilians, as well as soldiers, were caught in the bombardments. The City Walls had to be repaired several times as the Parliamentary cannons blasted at the Newgate, Water Tower and Morgan's Mount. At Morgan's Mount a huge attack caused a breach in the Walls, and the City was only saved by the action of a foreign volunteer soldier, the Compte de St. Pol who rallied the Royalist troops to fight back. Near the Newgate the Parliamentarians managed to breakthrough the Walls again. But they still failed to invade the city as they were killed as soon as they tried to climb through the gap caused by their cannon balls. When night fell the women of Chester came out to repair the Walls, as the men were exhausted from the battle.

The Siege of Chester

Life for the people of Chester was very hard during the siege. Not everyone in the city was a soldier. Along with the huge garrison stationed there to defend the city, women, children and grandparents were still living in their homes trying to carry on a normal life.

The Parliamentary forces camped outside the city bombarded Chester with cannon balls and burning missiles. Almost every house in Eastgate Street and Watergate Street was damaged. The people who lived in them were often hurt or killed during the bombardments, Sometimes a family would be hiding in the cellar when their house collapsed on top of them, crushing them to death.

All around the City Walls ditches had been dug for extra defences. But after a while these filled with stagnant water which overflowed and ran into the cellar's of people's houses. This was very smelly and unpleasant for the people who lived there, and could be dangerous too, because the water could carry dangerous diseases like cholera.

To pay for the soldiers who were defending their city, and all the extra defences that had been put up, the people of Chester had to pay high taxes. This was very hard for them because they usually earned their money from trade, but the Parliamentarians camped outside stopped traders coming to the city. Instead the people had to give all their savings as taxes, and lots of the silver treasures of the city had to be melted down to make coins.

Because there was very little trade during the war, the people of Chester soon began to run out of food. They managed to get supplies from supporters nearby, especially from Hawarden Castle in North Wales. But food was still scarce, and there was very little choice of what to eat. In the end the Parliamentarians stopped these supplies of food from getting in, and even the Mayor of Chester was forced to dine on boiled wheat and spring water.

King Charles and the Battle of Rowton Moor

King Charles visited Chester twice during the civil war. The first time was in 1642, shortly after the war began. His visit caused huge celebrations as he rode through the Eastgate to the cheers of the crowd. Anyone would have thought that he had won the war, and was popular throughout the country.

The King's second visit was in 1645 when he stayed in Gamull House, in Bridge Street. In those days it was the home of the wealthy Gamull family who's influence had helped Chester support the King's cause. By this time the war was going badly for Royalists all over the country, as the King's troops kept being beaten in battles. For this visit the king had to sneak into Chester without being seen by the Parliamentarians camped nearby.

While the King was in Chester for the second time another battle broke out nearby. This was the Battle of Rowton Moor, and was fought on 24th September 1645. To get a good view of the battle the King climbed to the top of one of the towers along the City Walls. In those days it was called the Phoenix Tower, but since the civil war it has been known as King Charles' Tower.

In those days it was called the Phoenix Tower, but since the civil war it has been known as King Charles' Tower.

The Battle of Rowton Moor was very long and hard fought. It was actually made up of three separate fights as the armies retreated and attacked again. The fighting lasted all day until the Parliamentarians, led by Colonel General Poynts, finally defeated the Cavalier troops.

Hundreds of Cavalier soldiers were killed, injured or captured at the Battle of Rowton Moor. As the King watched his troops run back to the safety of the city gates even he was nearly killed as a Parliamentarian fired at the group of men on the tower killing one of the King's companions. The King was very depressed by what had happened during the visit, and told Chester's commanding officer, Lord Byron, to surrender to the Parliamentarians if no help arrived within 20 days. After that he allowed himself to be smuggled away to safety again.

Chester Blockaded and Starved

After the Battle of Rowton Moor and the brief visit of King Charles, the situation looked very bad for the people of Chester. When the King left the city he gave the Governor Lord Byron instructions to surrender if no help arrived within 20 days. As the Royalist armies were now engaged in the south, the chances of Chester getting reinforcements looked slim. However, after holding out against the Parliamentary forces for nearly three years, the people of Chester were determined not to give in.

After their success at Rowton Moor the Parliamentarians who were camped outside the City Walls tried to break in again. However, the defences were too strong and eventually they realised that they would never win Chester by force alone. As winter approached and the Royalists inside the Walls waited in vain for reinforcements, the Parliamentarians decided to try a blockade to force the city into surrender.

Throughout most of the war Chester had been able to get supplies of food from nearby supporters, especially those in North Wales. Most supplies came from Hawarden Castle. This had been recaptured by Royalists after December 1643 following brief occupation by the Parliamentarians.

However, during the winter of 1645-6 the Parliamentarians blockaded the City of Chester and prevented any food reaching the inhabitants. Although there were some supplies within the city, they soon ran out. The people inside were forced to eat cats, dogs and even rats, to keep themselves alive. But the people of Chester still started starving to death.

Chester Surrenders

By the beginning of 1646 the whole of Chester was close to starvation. Many people had already died, and those left alive realised that they would have to surrender. It was nearly four months since the King had left the city following the Battle of Rowton Moor. Although no help had arrived the people of Chester had fought on, ignoring the Parliamentarians calls for their surrender.

Eventually though, they had little choice. On 26th January 1646 the Governor of Chester, Lord Byron, agreed to an honourable surrender. The sick and wounded were allowed to stay in the city until they recovered, and the able bodied could leave in safety. Chester officially surrendered to the Parliamentary forces on 3rd February 1646.

The Parliamentary leaders had promised to respect ancient buildings and Churches in Chester. But when their soldiers marched through the City Gates in triumph, they ran wild. During the Parliamentary occupation of Chester many Churches were damaged, and the High Cross was destroyed.